Thursday, October 7, 2021

When we have experienced emotional or physical or relationship damage in the past, it can continue to feel frustrating at best and irreparably harmful at worst. I so often look at the broken places as problems, limitations, and inadequacies. Or I try to ignore them. But the kintsugi approach actually highlights the beauty in repairs.

When we have experienced emotional or physical or relationship damage in the past, it can continue to feel frustrating at best and irreparably harmful at worst. I so often look at the broken places as problems, limitations, and inadequacies. Or I try to ignore them. But the kintsugi approach actually highlights the beauty in repairs.

The Japanese word kintsugi describes the ancient art of repairing broken pottery by mending the areas of breakage with lacquer dusted or mixed with powdered gold, silver or platinum. Kintsugi takes a broken piece of pottery, and uses precious and beautiful lacquer to highlight all those places where the breakage happened. The end result is something that many would say is even more beautiful than the pristine original.

Kintsuge treats breakage and repair as part of the history of an object, rather than something to disguise. Reflecting on this is helpful for me. The kinds of damage we can experience can include things like emotional abuse, physical illness or injuries, treatments for cancer, relationship break-ups, or forced relocation.

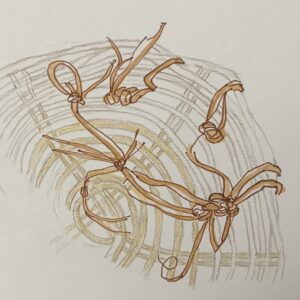

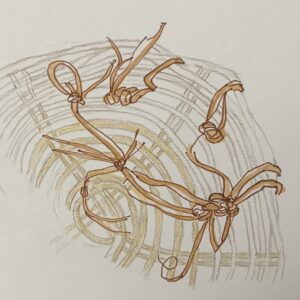

I have had a laundry basket for decades. The lid has slowly been breaking apart at the edges. I decided to repair it using raffia pieces that came in some packaging. I tied the raffia pieces to the edge places where it was breaking to hold them together. This is a drawing of the result. Someone commented on this drawing, and said that it looks like the raffia pieces are dancing. I can look at this basket lid, and reflect on the same for my life. I can react to the injuries, and make beauty, and creatively respond. Fully acknowledging the injuries, the hurts, the damage, but also reveling in the dance of my responses.

Harold Wilke was a stately older man, and I was having a lively and personal conversation with him and others over cocktails before a meeting at the National Center for Rehabilitation Research in Washington DC years ago. I continued the conversation as I sat next to him at dinner. We had been eating for a while and chatting, and then I suddenly noticed that his fork and knife were being held by his white-gloved feet. He had no hands or arms.

The relaxed graciousness of his presence impressed me. If I did not have arms and hands I would miss so many things. Shaking hands with people on meeting them. Hugging those in distress. Touching with my fingers those I love. Playing the piano. And all of those things don’t even address having to find other solutions to opening doors, taking notes, cooking, using a computer or texting. When I think of blessings that I am thankful for, I do not usually think of my hands. If I did not have arms and hands, I would hope that I would have the quiet gracious presence of Dr. Wilke. It was as if he was more fully human.

Jean Vanier inspires me. He started the L’Arche communities. They bring people who are marginalized and restless from lack of community and care, together with those who learn to care for them. They especially create small caring communities for those who have developmental disabilities.

Jean Vanier inspires me. He started the L’Arche communities. They bring people who are marginalized and restless from lack of community and care, together with those who learn to care for them. They especially create small caring communities for those who have developmental disabilities.

I met Jean Vanier over 30 years ago while living in Belfast, Northern Ireland. A small room of about 20 people had gathered to hear him speak and talk with him. Meeting him made a strong impression on me, and I followed up by reading anything by him I could get my hands on. He was from an important political family in Canada, had served in the Navy in WWII, and then pursued a PhD in philosophy. It was after this that he came to establish the L’Arche communities. As he spoke of the gift that those who had mental developmental disabilities were to him in his life, it helped me to see that what I had most valued in myself up to that time, my intellectual abilities, were not the most important thing in my life. The communities he started were based on mutual respect – those with developmental disabilities have things to share with us, things they can teach us, things they can give us. His life demonstrated how he really valued all people. We all have different gifts, and discovering those is an opportunity for each of us.

In addition to his writings on disability and community, he has also described human freedom in ways that I have found worth pondering. In his book, Being Human, he wrote: “Aristotle talks of our passions as being like a horse which has a life of its own. We are riders who have to take into account the life of the horse in order to guide it where we want it to go. We are not called to suppress our passions or compulsions, nor to confront them head on, nor to be governed by them, but to orient them in the direction we want to go….We set out on the road to freedom when we no longer let our compulsions or passions govern us. We are freed when we begin to put justice, heartfelt relationships, and the service of others and of truth over and above our own needs for love and success or our fears of failure….”

Saturday, August 20, 2011

The Human Being as revealed more fully in Disability and In Extremis. Lynn Underwood. European Research Network meeting: The human person in the 21st Century. Thessaloniki, Greece, April 22-25, 2007.

Abstract:

Interaction with people with severe disabilities and chronic disease, people at end of life, and people in other dire circumstances can inform our understanding of the human person. This can happen through personal and professional interactions and in the context of scientific research. Direct experience of dire circumstances in our own lives can also contribute to insight. When combined with theological, philosophical and artistic explorations these interactions and experiences can lead to further reflection on the core, or “heart,” of the human being, revealing the nature of the human being more fully. This exploration could also provide us with some questions to pursue in greater depth using the tools of the sciences and the humanities.

Various illusions and assumptions do not hold up as people are exposed to situations such as disability, extreme suffering or experiences at end of life. These include assumptions concerning self-sufficiency, functionalism, the place of suffering, the ability to control and mortality. People with disabilities have learned that receiving help does not diminish who they are and that it can actually enhance the human person. Likewise, the disabled person is at a disadvantage in the world constrained by functional evaluations. This realization can expose the fundamental value of a human being as not necessarily identical with their functional status or their physical selves. Suffering can encourage people to draw on the religious sphere, and open sufferers and others to the reality of the spiritual and its intrinsic importance in life. In the process of suffering one can see more clearly that there is more to a full life than superficial happiness and the pursuit of that happiness. When disabled, suffering serious chronic disease or in other dire circumstances, it becomes obvious that we are not in control and we are forced to see that sense of control is a delusion. The realization that death is inevitable affects how someone views life itself, and the fundamental nature of the human person. Being faced with these situations in extremis can more fully reveal the full nature of the human person.

Return to “Recent and Current Presentations”

When we have experienced emotional or physical or relationship damage in the past, it can continue to feel frustrating at best and irreparably harmful at worst. I so often look at the broken places as problems, limitations, and inadequacies. Or I try to ignore them. But the kintsugi approach actually highlights the beauty in repairs.

When we have experienced emotional or physical or relationship damage in the past, it can continue to feel frustrating at best and irreparably harmful at worst. I so often look at the broken places as problems, limitations, and inadequacies. Or I try to ignore them. But the kintsugi approach actually highlights the beauty in repairs. Jean Vanier inspires me. He started the L’Arche communities. They bring people who are marginalized and restless from lack of community and care, together with those who learn to care for them. They especially create small caring communities for those who have developmental disabilities.

Jean Vanier inspires me. He started the L’Arche communities. They bring people who are marginalized and restless from lack of community and care, together with those who learn to care for them. They especially create small caring communities for those who have developmental disabilities.